B-Side: The Amex Effect

This episode might reference ProfitWell and ProfitWell Recur, which following the acquisition by Paddle is now Paddle Studios. Some information may be out of date.

Please message us at studios@paddle.com if you have any questions or comments!

The AMEX effect and its impact on pricing

Pricing is at the very core of your business. No matter what type of product you're selling you've created some sort of value, and since we don't trade goats for wheat anymore (at least in the economies we all play in), you ascribe some sort of currency amount to that value.

Your pricing is the exchange rate on that value. You can influence that exchange rate in many ways—higher value features and better packaging, selling to different types of customers who value the product more, charging based on some element of usage, and the list goes on.

You'd think something so central to the very reason our business is in existence would get a lot of attention, right?

Well, no.

Pricing is basically the fruits and vegetables of growth. Crucial to your success and can definitely make the journey quicker and easier, but not as exciting when you have access to a world of processed sugar, salt, and fat. We're pretty terrible at getting our greens as an industry. We think pricing is an exercise harangued once every three years when our board yells at us or someone wakes up and realizes there's a better way to grow.

I've been writing and speaking about pricing for almost a decade now, trying to rally the market into realizing the best companies in the world are doing their research and changing something about their monetization every three months.

While most days I feel like Demosthenes shouting at the ocean, I think the problem ultimately comes down to me. To continue the faulty metaphor, I need to smear some cheese on this broccoli. I've been trying to teach you the strategy and fundamentals, when you could benefit from some tactics that can be easily and quickly implemented.

With that in mind, here's the culmination of a bunch of research around something we coined as "the AMEX effect" that we've studied across 3.2M consumers at this point and will help you tactically improve your pricing with very little work (I'm upset this made me sound like an informercial, but this is where we are now).

The AMEX effect is also responsible for some of the most interesting purchasing quirks out there:

- Why you've paid for delivery from a restaurant that's four blocks away from you

undefinedundefined

As a business, the AMEX effect can be extremely powerful in helping your conversion rates and overall monetization strategy. As a consumer, it can also help you realize when you're getting strung along a bit too much. Regardless, this should be helpful. So let's jump into defining the phenomenon a bit more before jumping into the data.

The AMEX effect is defined as the point at which your customer is more than willing to swipe their credit card without much thought or decision-making effort. Put more simply—it's the price point at which your target customer won't scrutinize the purchase.

Why does the AMEX effect exist?

Us humans think about pricing and value on a spectrum. We know certain items are around a certain amount because we've purchased similar items in the past, or we at least can stack an item's value in the context of other things we value very quickly. This is also why we're pretty terrible at pin pointing the exact price of an item. There's a reason why contestants on the Price is Right statistically win more when the game involves guessing if an item is more or less expensive than another item or price point, rather than when the game requires them to know a box of soap is worth "$3.82." [1]

Our personal circumstances also impact our perception of value greatly, particularly when it comes to age or income. When you were a kid and earned that small allowance doing chores, the idea of purchasing your first computer seemed daunting. Yet, most of you with full-time employment today have no problem purchasing a $5 latte multiple times per week.

My personal favorite example here is when people ask billionaires, like Bill Gates, the prices of grocery items. He hasn't been to a market in decades and his wealth gives them wildly incorrect answers—typically 5x the price of a gallon of milk or loaf of bread.

While many factors fit into the calculation of the AMEX effect for your target customer, when we run the numbers, the primary axis typically comes down to income when looking through consumer or prosumer products, and seniority when it comes to B2B products. Here's a breakdown of the AMEX effect by income. Put another way, this data answers, "What's the dollar amount where you'd start to think more about the purchase?". A more business focused question that's answered here is, "For a target customer, at which price will they think the least?"

Keep in mind these are likely starting points to get the first dollar. Once you're in, it's easier to expand. In this light is where things get a bit fascinating.

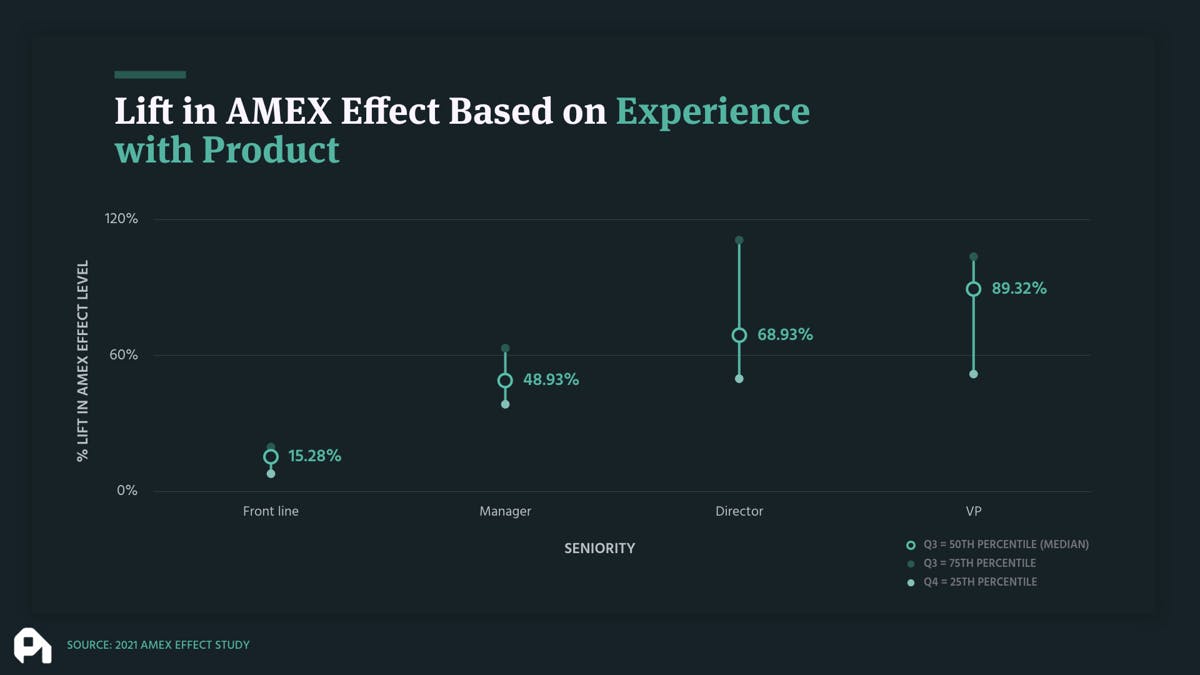

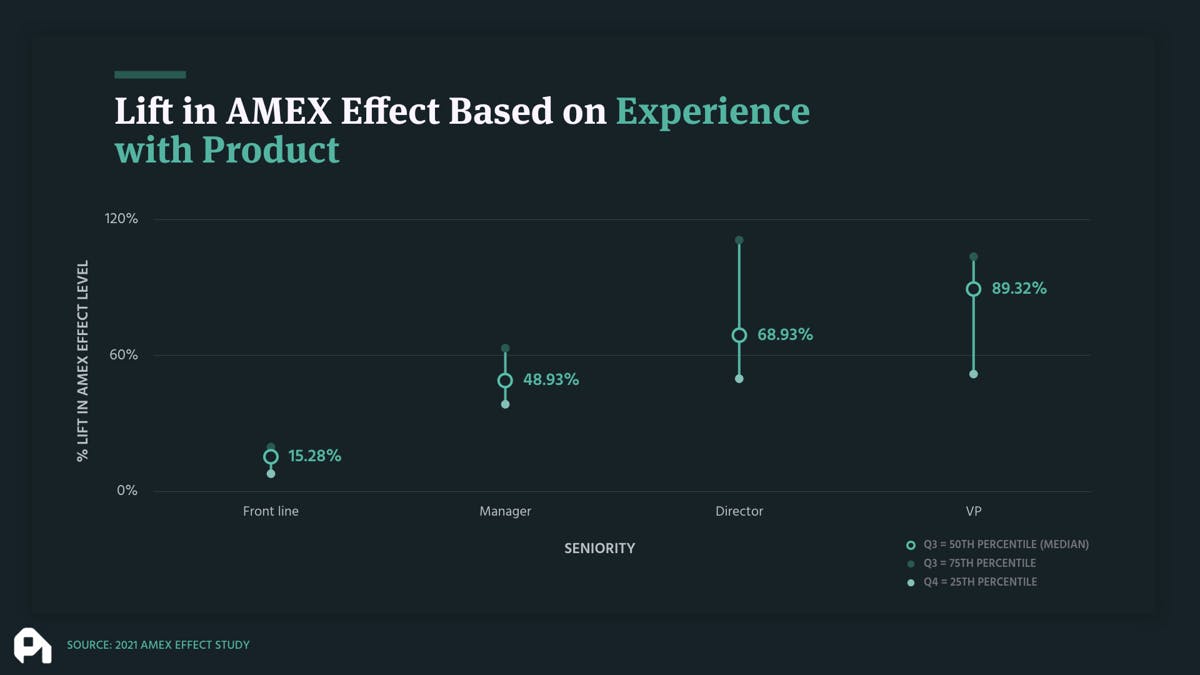

The experience with the product greatly influences where the AMEX effect hits. For instance, let's separate out two types of B2B purchasing experiences. Someone who's about to purchase after using a freemium version of the product vs. someone who's about to purchase from just viewing the marketing of a product. Below you're seeing the lift in willingness to pay for those who used the freemium version of the product, relative to those who hadn't used the product at all yet.

Notice how the AMEX effect is significantly higher for the individual who used the freemium version of the product. Why? They already have clear signal that this product is worthwhile and worth quickly swiping a credit card on. Their perception of value increased due to their circumstance. A lot of you give me guff for my stance on freemium being in every company's future, but this is another reason why that's the case.

Now let's look at a consumer scenario. We did a small study looking at the AMEX effect's different baskets of consumer products—food, beauty/cosmetics, apparel, etc. We took measurements before the person put together their cart of goods, and then right before the swiping of the credit card.

Notice how the folks who went through the trouble of picking out items had a much higher AMEX effect than those at the beginning of the purchase cycle. Our experience and buy-in changes our perception, because we're typically making micro decisions based on will and want versus logic. The result—we end up being ok to pay more. My particular favorite here is what I like to call the "hunger peak." Notice how in the food/beverage category the range gets pretty high. In looking at the data, that's being pulled up by food delivery scenarios where someone just needs to get the product so they'll pay (mostly) anything.

The phenomenon in the above graph is the reason food-ordering apps don't show you the fees until the end. Starbucks shows absolutely no prices until you reach the point where you want to place your order. Tailors and haberdasheries have for years gotten you to buy-in to the suit and then ask you to purchase the shirts, ties, etc. Larger products anchor you with buy-in and then take advantage of your lizard brain to get you through the conversion.

Implications for your business—what should you do with this information?

- Rethink your payment funnels to encourage buy-in before price evaluations

One of the biggest tactics to think through in the context of the AMEX effect is to rethink how upfront you are with the pricing of your products. I'm not saying go opaque and take down your pricing page. Yet, there's likely a case to be made for asking a user or customer if they'd like an add-on and not showing that price point until the cart. We haven't seen this much in the world of B2B, but it's a commonly used practice in retail and consumer products. You'll end up with some folks taking it out of the cart, but you'll have more people buy-in, increasing revenue per customer and lifetime value.

Another big piece here is just another reminder to start using an add-on strategy. It's one of the most underutilized pieces in a monetization strategy. In this case getting folks to buy-in and then showing them the add-ons of priority support, extra analytics, more seats, etc., will likely increase your adoption rate, thereby increasing your revenue per customer and lifetime value. - If your product is $30 per month or below, your annual price should look into the AMEX effect

Annual subscriptions have 30% higher retention than monthly subscriptions, especially when dealing with lower priced products. Right now if you have a lower priced offering, the annual version of that should hit one of the AMEX effect price points we spoke of, and you should heavily offer this in the onboarding or initial purchase process. To be clear—you should price your annual plan at $100, $150, $200, or $250.

Assuming your LTV is average here, don't worry about the size of the discount. The uptick in folks grabbing the product at their AMEX effect will justify any missing optimization in discounting threshold. - Treat product-led growth, and growth in general, as a multi-move game

Too many of us are just chasing the initial sale—to the point that we're being penny wise and pound foolish. If you can lower your customer acquisition cost, boost your retention, increase your NPS, and double the amount your prospects are willing to pay by letting them play around with the product for a month for free. Why in the world wouldn't you do it? Freemium is the future. It's the best content you have, so you should use it to bring customers into the fold.

But PC, some guy who sold a database company in 2006 is telling me I'm ruining my product's value if I give something away for free. He has a corvette -shouldn't I listen to him?"

No. No data supports that notion.

More broadly, we need to stop listening to the hotshots who built their businesses in a time when the recipe was as archaic as: raise money, dump it into channels, go public, profit. It's a great strategy when you could fit every tech company in existence in a pretty little powerpoint deck, not when companies are replicating mitotically like the cells of the body.

Old-school growth was a single move endeavor. New-school growth is multi-move. It requires you thinking through the steps of a prospect, not just dumping acquisition down your gullet.

Ok. I'm starting to get aggressive, which is hopefully entertaining, but also the point where I know it's time to wrap up. Ultimately, pricing comes down to understanding who you're trying to sell to and making sure you're providing them value. It's a beautiful, symbiotic relationship, especially in the subscription world where the relationship is baked directly into how you make money.

Take pricing more seriously. We didn't even get into how improvements in pricing have 4-8x the revenue impact than similar improvements in pricing, but feel free to reply here if you'd like the book I wrote on pricing, which goes deeper into monetization strategy and that data, as well.

[1] For our non-US readers, the Price is Right is basically the most American game show ever. Contestants guess the prices of items in order to win the items, or more valuable items. Capitalism at it's finest and it's been on television for decades.

Do us a favor?

Part of the way we measure success is by seeing if our content is shareable. If you got value from this episode and write up, we'd appreciate a share on Twitter or LinkedIn.

00;00;00;04 - 00;00;01;27

Patrick Campbell

Let's put some cheese on this broccoli.

00;00;03;08 - 00;00;25;22

Ben Hillman

From proper well recur, it protects the hustle where we explore the truth behind the strategy and tactics of B2B SaaS growth to make you an outstanding operator. On today's episode, we're diving deep on an analysis of the Amex effect, which is a phenomenon of pricing at the point where your customer doesn't think much about the purchase. We'll be walking through how to take advantage of this, including all the data.

00;00;25;26 - 00;00;27;09

Ben Hillman

Patrick, take it away.

00;00;29;09 - 00;00;50;10

Patrick Campbell

Welcome back. To Protect the Hustle, the B-sides voice you're hearing. This is Patrick Campbell, CEO, founder of Profit. Well. Today we are going to be talking about something we've been researching for quite some time. We coined it defined a few years back, and it's known as the Amex effect, which is essentially the point at which you can price where your user, your customer won't really scrutinize the purchase that much.

00;00;50;11 - 00;01;08;06

Patrick Campbell

It's the reason why all of us have probably fallen prey to paying for food delivery from a restaurant that's only a few blocks away, or use that Uber or Lyft ride for only a few blocks as well. It's also the reason why there's credit card charges on our credit card statements that basically all add up and there's no one purchase.

00;01;08;06 - 00;01;21;10

Patrick Campbell

But we kind of feel like, Oh, why is our credit card bill so high? It's also the reason why some people purchase subscriptions and they only use the product for a month but then end up paying for it for eight months. So we're going to explore this to make you kind of a stronger consumer, but also to help you in your business.

00;01;21;10 - 00;01;42;12

Patrick Campbell

But a couple of other housekeeping items. I'm going to be traveling from Salt Lake City to Miami and back over the next couple of months. I'm going to be doing this by car essentially with my better half, and we're going to be stopping in a bunch of different places. So if you're in different tech hubs or just want to hang out and you're somewhere on the east half of the United States, feel free to hit me up.

00;01;42;12 - 00;02;01;04

Patrick Campbell

We're probably going to be going to kind of the obvious hotspots in Texas, New Orleans, some of the places in like Kansas City, Nashville, Atlanta, etc.. But if you're listening to this and you want to hang out in a safe way, just let me know. It's kind of weird to say a safe way, but all of you know what I mean, in the context of COVID, socially distance, all that jazz.

00;02;01;06 - 00;02;27;01

Patrick Campbell

Also, we released a couple of new features for Retain Our Product that basically plugs into your billing system and reduces your cancellations and churn if you're interested in those or want to check that out. Now is probably the time to completely pay for performance. It's turnkey and we're getting to the point where we're getting really, really good, you know, reducing churn by, you know, at least 20%, if not more, because we're going after not only credit card failures, but also active cancellations as well, through some pretty cool technology.

00;02;27;02 - 00;02;44;24

Patrick Campbell

And then finally, our media team would hit me or come and steal my zoom. I don't know what they would do considering we're not all in the same place. But media team wants some feedback here. Is this interesting? Are you enjoying this content? Are we doing a good job? Is this valuable? If not, what could be better? If it is, what could be better?

00;02;44;24 - 00;02;58;29

Patrick Campbell

If you could kind of reply to the email? If you're not on the emails, just go to protect the hustle dot com and sign up. There's a written version of this that's sent out in addition to the audio version. That would be awesome. And if you could share this in a social media channel of your choice, that would be amazing as well.

00;02;58;29 - 00;03;21;08

Patrick Campbell

That's one of the ways we're measuring success. Just want to see this get into the hands of as many people as possible. And with the housekeeping aside, let's jump into the mix effects. So to kind of take a step back, I want to, you know, kind of put the AMC's effect in context, because as you've probably known, if you follow anything that I write or anything I talk about, pricing is at the very core of your business.

00;03;21;08 - 00;03;39;29

Patrick Campbell

And no matter the type of product that you're selling, you've created some sort of value. And because most of our economies don't trade goats for wheat anymore, you ascribe some sort of currency amount to that value. And this is why I like to say and like to kind of provide context at the 30,000 foot view level, your pricing is the exchange rate and the value that you've created.

00;03;39;29 - 00;03;57;19

Patrick Campbell

And in that context, you can influence that exchange rate in many different ways. You can add different features, you can change how you charge, you can localize your pricing, you can use a value metric. The list kind of goes on endlessly. And you'd think because it's so central to the very reason you're in business, that monetization would get a lot of time and attention.

00;03;57;19 - 00;04;21;07

Patrick Campbell

And of course it doesn't. And it's basically the fruits and vegetables of growth, right? It's crucial to your success can definitely make things go easier and quicker, but it's not as exciting to the world of salt, sugar and fat that we have access to these really cool acquisition channels, cool social post blogs, all these different fun things that are presumably easier to do, don't have as high of an impact on our lives, our health, our businesses health, if you will.

00;04;21;07 - 00;04;41;17

Patrick Campbell

But there are a lot more fun, right? And you know, to put it more simply, we're just terrible at getting our greens as an industry. We think pricing is this once every three years exercise when our board yells at us or you know, there's something on fire. And I've just been writing and speaking about pricing for almost a decade, you know, trying to rally folks around this concept and, you know, have learned that the best companies out there, they have a balanced growth approach.

00;04;41;17 - 00;05;00;12

Patrick Campbell

They're still spending half their budget and half their time on acquisition. You know, the sugar, salt and fat of growth. But in addition to that, they are also spending time on, you know, their retention and their monetization, and they're changing something about their pricing every three months. And, you know, this kind of Sisyphean task or, you know, I feel like the the is, you know, shouting at the ocean if you don't know our demands.

00;05;00;12 - 00;05;19;29

Patrick Campbell

And he says he's definitely worth a Wikipedia read. But I think the problem in kind of hindsight and rethinking, especially going into 2021, is me. And what I mean by that is, you know, to kind of continue the faulty metaphor is I need to smear some cheese on this broccoli I've been trying to teach you, you know, the broccoli I've been trying to teach you, you know, proper nutrition, all these other things.

00;05;19;29 - 00;05;41;18

Patrick Campbell

But I'm not making it easy for you to basically implement and get some momentum. And so what I'm trying to do in 2021, especially when it comes to pricing research and publishing different, you know, pricing studies, is give you things that can be quickly implemented and that can help you. And that's where the Amex effect comes in. It's a combination of a lot of research data from somewhere around 3 million different consumers at this point in the composite study.

00;05;41;18 - 00;06;03;17

Patrick Campbell

And it's something that will really tactically help you implement, you know, better pricing strategy. And as a business, the Amex effect is extremely powerful in helping your conversion rates and making sure that you're getting those first dollars very, very quickly. So let's jump in. Define this phenomenon a little bit more, understand where it comes from in the grand scheme of, you know, human psychology and economics and then ultimately talk about some data.

00;06;03;17 - 00;06;17;16

Patrick Campbell

And if you want the actual data readouts, either go to my Twitter feed because I'll have tweeted about this when it's released, or feel free to just go to protect the host dot com and make sure you signed up for the actual email newsletter, which includes the graphs as well as a write up of everything that I'm talking about.

00;06;17;17 - 00;06;46;13

Patrick Campbell

So, okay, let's start with why. Why does the mix effect exist? So this requires us to understand how human beings think about value and think about pricing. So as human beings are, we're just very bad at understanding, you know, price points. We think about pricing and value as a spectrum. So we know that certain items are worth certain amounts because we've either purchased those items in the past or similar items in the past, or if we haven't, we're at least pretty good at stacking, you know, kind of ranking items value.

00;06;46;13 - 00;07;00;25

Patrick Campbell

So what I mean by this are to bring this to life a little bit. There's water bottle sitting on my desk right now. We know that that's worth less than the computer that I'm recording this on. We know that for a whole host of reasons, one of which we purchased these items in the past. But to like the utility of those items is definitely different.

00;07;00;25 - 00;07;13;20

Patrick Campbell

You know, water's more of a commodity. Even if I like the water bottle that I'm using, you know, if I lose it, it's not the end of the world right now. If you change my circumstance and this is an important point and all of a sudden I'm in the desert for three days without water, all of a sudden that value differential really switches.

00;07;13;20 - 00;07;30;05

Patrick Campbell

Right. And there's actually an interesting phenomenon here. And whenever I can reference the prices, right, I feel like I need to. But there's a game show in the United States. For those of you who aren't U.S. based, you know, we have a really good international following here where basically the whole premise of the game is to gas prices and it's just peak American capitalism.

00;07;30;05 - 00;08;01;18

Patrick Campbell

It's great. It's been on for decades, multiple different hosts at this point. But the basic idea is you win prizes based on how good you are at understanding value and understanding price points. And what's really kind of interesting to kind of, you know, kind of support this point is that they've shown that statistically contestants on the game show win more when the game that they're playing the mini game on the show that they're playing involves guessing if an item is more or less expensive than another item rather than if the game involves them having to actually figure out a specific price point.

00;08;01;22 - 00;08;17;12

Patrick Campbell

Put another way, when they have to understand a specific price point, they lose a lot more versus when they can say, Oh, that item is worth more than that item, which, you know, those are the two premises of most of the games on that show. So I already mentioned that our personal circumstance and our personal situation can affect things.

00;08;17;12 - 00;08;42;03

Patrick Campbell

And this is actually really interesting relative to two main axes, age and income when it comes to, you know, general human value differentiation. So, you know, put another way, when you were a kid, you got a small allowance for doing chores. The idea of purchasing a computer or even a big Lego set or something like that, it seemed really daunting, right, because you were only getting a dollar a week or I don't know what kids get these days, but I think I only got like a dollar a week until I got a paper out and these other things.

00;08;42;03 - 00;09;01;09

Patrick Campbell

And most of us, as we grew up, now most of us are hopefully gainfully employed or at least know what it's like to be gainfully employed, you know, epidemic aside, it's interesting that what we find is we're more than willing to purchase things like $5 lattes multiple times per week because we have a steady paycheck. And this is kind of that income that's really easy to purchase.

00;09;01;09 - 00;09;21;26

Patrick Campbell

And my personal favorite kind of example here is when people ask billionaires like Bill Gates the price of common grocery items, and this was something that was done on the Ellen show, I think some other folks have done it with other, you know, billionaires out there. But, you know, someone like Bill Gates hasn't been to a supermarket in decades and his wealth has basically giving him just wildly incorrect context on how much things actually cost.

00;09;21;26 - 00;09;38;00

Patrick Campbell

So when people ask him, hey, what's the price of a gallon of milk or what's the price of a loaf of bread? Typically his answers are like five times reality, because again, he just doesn't have good reality on how much things cost. And so when we get into the mix effect here, there are a lot of factors that can fit into the calculation for your target customer.

00;09;38;00 - 00;10;03;14

Patrick Campbell

But when you run the numbers, the primary access typically for consumer side comes down to income. And then when we look at B2B, it comes down to the seniority of the person inside the organization. So the first breakdown we're going to talk about for the Amex effect is essentially consumer purchasers and looking at it by income. So put another way with this data answers is what is the dollar amount where you'd start to think about the purchase and business perspective?

00;10;03;14 - 00;10;27;18

Patrick Campbell

It's for a target customer at which price will they think the least and convert at the highest rate. Now it's a little bit harder to describe graphs on a podcast, so I'd encourage you to check out the actual write up, but we're going to do our best here. And so what we have is a graph that essentially is looking at different consumers for based on their income levels and essentially where their Amex effect is, where is their willingness to pay, where they don't really think about the purchase.

00;10;27;18 - 00;10;49;17

Patrick Campbell

Now, when we look at consumers who are making somewhere between zero and $50,000, you're essentially seeing that the Amex effect is right around $20. And this is why a lot of infomercials will be 1999, right? Because they go through the motions. They talk about all the objections, and then they say 1999. And if you look at consumers for 51 to $75000 in annual income, they're Amex effect is right around $50.

00;10;49;19 - 00;11;13;06

Patrick Campbell

Now, what's interesting is that for these less affluent customers, these consumers, they tend to have a very hard feeling. Put another way, if you're going after someone who makes less than $75,000, you're essentially going to run into some issues. If you try to go over the $20 price point or the $50 price point, mainly because what ends up happening is that you actually are running into kind of, you know, them starting to really, really think about things.

00;11;13;08 - 00;11;29;28

Patrick Campbell

Now, if your price point is lower, you will tend to get more people to actually purchase. Now you don't need to go lower, but there's higher variance. Essentially on the low end. They have a very loose floor and a very, very strong or very hard ceiling. Now the opposite effect takes place when we get over $75,000 in income.

00;11;30;00 - 00;11;49;19

Patrick Campbell

Put another way, those folks who are making over 75,000, depending on the bracket, they basically when we look at their Amex effect price point, for instance, for the folks between 75 and $100,000 in annual income, their Amex effect is basically at $100. But they basically have a hard floor, like if it's under $100, they're still not really thinking about it.

00;11;49;19 - 00;12;08;05

Patrick Campbell

You don't really need to go much lower than $100. But there's a really, really loose ceiling, meaning some of those folks, $150 isn't, you know, anything to them. Sometimes $200 isn't anything to them. And the effect basically kind of plays out as we look at brackets of people from 150 to $200000 in income for even people at 200,000 or more in terms of annual income.

00;12;08;05 - 00;12;28;23

Patrick Campbell

And so the basic idea here is the higher the income, the stronger the floor in the ranges, meaning if you have a target customer in that range, it's safe to say that that's a really solid price point. As I already mentioned, lower income folks have weaker floors and stronger ceilings, meaning there's a more variance going towards zero. Practically, this means you can experiment going higher with affluent folks, the less affluent folks.

00;12;28;23 - 00;12;43;19

Patrick Campbell

There isn't a lot of wiggle room. Now, the other thing to kind of keep in mind here is that it's not as simple as just putting a payment form in front of their face. They need to be somewhat interested in the product or have some level of demand. The lift doesn't have to be that heavy, though. Again, this is why infomercials are, you know, very, very good, very, very persuasive.

00;12;43;19 - 00;13;02;25

Patrick Campbell

And the price point is right within this Amex effect for consumers. You also have to keep in mind that it's one of those things where depends on how deep your rabbit hole goes in terms of value. So what I mean by that is if you have, you know, something where your positioning is terrible, your actual product has bad reviews and all these other things like the Amex effect isn't going to help you.

00;13;02;25 - 00;13;15;06

Patrick Campbell

So there's some assumptions here that were kind of looking at the average or the middle of the road. And then when you look at your business, you are still going to have to make a bit of a judgment call. But if you've done mostly the right things, all of a sudden this is a really, really good guide for you.

00;13;15;08 - 00;13;33;27

Patrick Campbell

Now, in a B2B context, it's a really similar trend here, but it's, as I mentioned before, more based on seniority. And so with the graph that we set up is we basically looked at early stage companies and then post early stage, which is obviously really wide range. And then we looked at the Amex effect for front line manager directors, and VP's essentially put another way like what price point are they?

00;13;33;27 - 00;14;05;01

Patrick Campbell

You know, not going to think about the purchase. Now what's really interesting is that when we look at noncore early stage companies, the front line basically is right around 50 bucks, but they have a really hard ceiling. The manager is right on $250 directors right around $500, and then VP is right around $1,000. And what's really kind of interesting here is that when you think about these purchases, what you're essentially seeing is, is if you're going to try to do sell a bottoms up product, depending on who your target is, you'd want to make sure that your price didn't exceed $50 if you're going after front line workers.

00;14;05;01 - 00;14;26;05

Patrick Campbell

And he also would want to make sure that your price was at like 250 or 500 if you're going after kind of managers and directors. Because essentially these folks, this is what their budget authority looks like. They're not necessarily going to scrutinize this particular purchase and they're not going to feel like they have to go get approval for this purchase if you're price at those price points or lower, essentially, and you also have to keep in mind that these are likely starting points to get to that first dollar.

00;14;26;05 - 00;14;52;24

Patrick Campbell

Once you're in, it's a lot easier to expand. And in this light, this is where things kind of get really, really fascinating because we continue kind of the study and the experience with the product greatly will influence where that Amex effect hits and exists. For instance, what we ended up doing is we separated out two types of B2B purchasing experiences someone who's about to purchase after using a freemium version of the product versus someone who's about to purchase from just viewing the marketing of the product.

00;14;52;24 - 00;15;10;05

Patrick Campbell

And what we noticed in the data and again, you can get the graph at Protect Hustle dot com or checking out my Twitter is that essentially those folks who had an experience with the freemium product, I mean they have actually used the product or a version of the product. They tended to have much, much higher willingness to pay or their Amex effect kicked in at a much higher rate.

00;15;10;08 - 00;15;33;17

Patrick Campbell

So frontline folks that were willing to pay about 15% more, which isn't much. But then when we get to managers, directors and VP's, they basically had more confidence in their decision and their willingness to pay or their Amex effect was 50 to 90% higher and in some cases broke 100% more willingness to pay. And the reason this is happening is they already have a clear signal that this product is worth while and worth quickly swiping that credit card.

00;15;33;18 - 00;15;52;20

Patrick Campbell

The perception of value is increased due to their circumstance. And I know a lot of you give me guff for my stance on freemium because I believe that it's in every company's future. But this is another reason why that's the case. And when we go a little bit deeper here and we look at kind of the consumer version of this, we did a small study looking at the Amex effect of different baskets of consumer products.

00;15;52;20 - 00;16;09;04

Patrick Campbell

We looked at food and beverage, we looked at cosmetics and beauty, We looked at apparel and fitness, and we basically took measurements before the customer put anything in their cart before they did any purchasing. So they had intent to come and purchase, but before they even experienced the website. And then we took it right before of the swiping of the credit card.

00;16;09;04 - 00;16;28;02

Patrick Campbell

So we measured the Amex effect in both of these places. And what was really kind of fascinating is that when folks went through the trouble of picking out items, their Amex effect was much, much higher. Our experience in our buy in basically changes our perception because we're typically making these micro decisions based on will and want versus actual logic.

00;16;28;02 - 00;16;47;13

Patrick Campbell

And this means we end up paying more when we look at the actual data. Basically the lift was about 20 to 30% when someone has actually experienced or put things in their cart or almost gotten to the end of the checkout. And my particular favorite here is when we looked at food and beverage, it actually had what I like to call the hunger peak, which is basically, you know, the range jumps to almost 40%.

00;16;47;13 - 00;17;05;03

Patrick Campbell

And this is largely being driven by like food delivery scenarios where someone just like needs to get the products will pay almost anything. Right. And what's kind of interesting is that this is phenomenon in the graph. And again, to protect our economy, you can check it out. It's the reason that a lot of food ordering apps will not show you the fees until the end.

00;17;05;06 - 00;17;27;27

Patrick Campbell

Starbucks actually does this in a dramatic fashion where they will not show you any price points like open up your Starbucks out. They will not show you any price points until you reach the point where you want to actually place the order. And this is a phenomenon that's been around for quite some time. The economists have studies where like tailors or haberdashery or people who sell men's suits, they will typically sell the suit first and then they will sell the shirts and ties and other things.

00;17;27;27 - 00;17;45;08

Patrick Campbell

These larger products that anchor you with this buy in, and then they take advantage of kind of your lizard brain to get you through the conversion. And so what are the implications for your business? You know, what should you do with this information to put it another way. So the first thing is you want to rethink your payment funnels to encourage more buy in before the price evaluation actually takes place.

00;17;45;09 - 00;18;06;10

Patrick Campbell

One of the biggest tactics to think through in the context, the Amex effect is to rethink how upfront you are with your pricing. Well, I'm definitely not saying like take your pricing page down. That's a whole nother discussion. But there's likely a case to be made for asking a user or customer if they'd like something like an add on or another piece of the product and not showing that price point until the cart or until the final kind of conversion.

00;18;06;10 - 00;18;22;24

Patrick Campbell

And we haven't really seen this as much in the world of B2B, it's a very common practice in the world of consumer products and you're going to end up with folks taking the item out of the cart. But I guarantee you you'll have more people buy in to that particular add on in this manner, which ultimately will increase your revenue per customer and lifetime value.

00;18;22;24 - 00;18;42;21

Patrick Campbell

And another big piece here is it's just another reminder to start using an add on strategy in general, it's one of the most underutilized pieces of monetization strategy. It's this, you know, in this case, it's getting folks to buy in and then showing them the add on of priority support, extra analytics, more seats, etc. It's going to increase your adoption rate and thereby increase your revenue per customer in lifetime value as well.

00;18;42;21 - 00;19;05;01

Patrick Campbell

The second big thing here is if your product is $30 per month or below your annual price should lock into the AMEX. In fact, annual subscriptions typically have about 30% higher retention than monthly subscriptions. And this is especially true when dealing with lower priced products. Right now, if you have a low priced product offering, the annual version of that should hit one of the Amex effect price points that are in the data that we showed or spoke about a little bit earlier.

00;19;05;01 - 00;19;23;02

Patrick Campbell

So to be clear, like you should price your annuals at $100, 150, $200 or $250. And the thing is, is that assuming your lifetime value is kind of average here, like don't worry about the size of the discount. Put another way, like if you're, you know, annual is actually going to end up being, you know, almost four months off.

00;19;23;02 - 00;19;39;28

Patrick Campbell

If you price at $200 for some reason, don't worry about the size of that discount. Normally I would worry about the size of the discount. But long story short, like the uptick in folks who are going to grab this product, given the Amex effect, it's going to justify any missing optimization in the discount strategy and threshold. It's a really, really big thing to think about.

00;19;39;28 - 00;19;55;22

Patrick Campbell

And this is why a lot of products that are lower price on a monthly basis, they end up having somewhere around like 50 to 60% of their contracts or their agreements or their payments be on an annual basis rather than just on a monthly basis. That's huge, huge thing to consider a good case study. There's like master class, right?

00;19;55;22 - 00;20;15;15

Patrick Campbell

Master class above $200 a year, and I think they only offered annual for quite some time before they actually offered up a monthly option. The third thing here is you got to treat your product like growth and growth in general as a multi move game. And this is kind of my subtle freemium point that I referenced before. I think too many of us are chasing that initial sale to the point that we're being very Penny wise and pound foolish.

00;20;15;17 - 00;20;30;23

Patrick Campbell

If you can lower your customer acquisition cost, you can boost your retention, you can increase your NPS and you can double the amount that your prospect is willing to pay by letting them, you know, kind of play around with the product for a month, you know, for free. Why in the world wouldn't you do it? Freemium is the future.

00;20;30;23 - 00;20;51;15

Patrick Campbell

It's the best content you have and all of the data supports what I just said. So you should use it in this context to bring customers into the fold. And I know like the common objection I get, this isn't exactly what it is, but most people are like, Hey, a PC, You know, some guy who sold a database company in 2006 is telling me that I'm ruining my product's value if I'm giving away something for free.

00;20;51;15 - 00;21;09;01

Patrick Campbell

You know, he has a Corvette, so should I listen to him? You know, I'm getting a little aggressive there. But no, like, the data does not support what he or she is saying. And I think more broadly, we need to stop listening to the hotshots who built their business in a time when the recipe was archaic. Ads raise a bunch of money, dump it into a bunch of channels, go public and profit.

00;21;09;01 - 00;21;33;26

Patrick Campbell

It was a really, really great strategy when you could fit every tech company that existed in a pretty PowerPoint deck. Now we have basically companies replicating methodically like cells and biology. And so the big thing here is that Old-School Growth was a really single move. Endeavor and this whole new school growth is multi move. It requires you to think through the steps of a prospect, not just dumping acquisition down your gullet because it's just not going to work out.

00;21;33;28 - 00;21;53;07

Patrick Campbell

We're seeing this time and time again there's a reason that so many products are quote unquote democratizing X or Y across an industry because it's one of the best acquisition strategies out there. And your freemium strategy does not need to be, you know, necessarily a product that is perfectly in line with the product that you're selling, as long as it's bringing in those customers.

00;21;53;07 - 00;22;06;14

Patrick Campbell

Now, if you can align those two, that's great. But even in the enterprise, if you have some sort of freemium product that brings in your leads and then you sell them the big contract, we're seeing more and more of that. All right. I'm going to call that down a little bit because I could rant about that all day.

00;22;06;14 - 00;22;26;09

Patrick Campbell

And I don't know if that's really interesting. If their answer interesting, I can get more ranty just to share with me in the email or on social, but ultimately pricing. It comes down to understanding who you're trying to sell to and making sure you're providing them value. It's a beautiful symbiotic relationship with that customer. You know, especially in the subscription world where the relationship is baked directly into how you make money.

00;22;26;09 - 00;22;49;23

Patrick Campbell

It's that important. And oftentimes it's one of those things that we don't think about our relationship with our customers enough. In that context, you got to take pricing more seriously. We didn't even get into how improving your pricing actually has a 4 to 8 impact in improving your acquisition. But you can reply here, I can send you that data and obviously I've written a ton, including a book on pricing which goes deeper into monetization strategy and the data to feel free to reach out.

00;22;49;25 - 00;23;02;12

Patrick Campbell

PC Prop welcome or hit me up on Twitter and we can go from there, but hopefully this was useful. If you want to see the data, go to protect the hustle dot com. Find me on social or reply or you know just email me a PC, a profile by comp or that have a good rest of the week.

00;23;02;12 - 00;23;04;04

Patrick Campbell

Be well we'll talk next week.

00;23;04;04 - 00;23;49;00

Ben Hillman

So yeah thanks for listening. If you enjoyed this episode, we'd really appreciate it if you left a five star review of this podcast or the equivalent rating wherever you listen or watch. Also, make sure you subscribe to and tell your friends about Protect the Hustle, a podcast from Al Roker, the largest, fastest growing media network dedicated to the world of subscriptions.